Spindle's End

Spindle's End The Door in the Hedge: And Other Stories

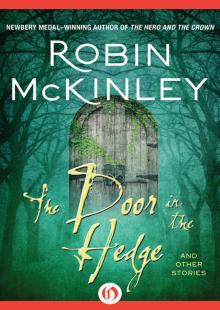

The Door in the Hedge: And Other Stories The Blue Sword

The Blue Sword Rose Daughter

Rose Daughter A Knot in the Grain and Other Stories

A Knot in the Grain and Other Stories The Hero And The Crown

The Hero And The Crown Deerskin

Deerskin Sunshine

Sunshine Beauty: A Retelling of the Story of Beauty and the Beast

Beauty: A Retelling of the Story of Beauty and the Beast Shadows

Shadows Pegasus

Pegasus Chalice

Chalice The Outlaws of Sherwood

The Outlaws of Sherwood Fire: Tales of Elemental Spirits

Fire: Tales of Elemental Spirits Beauty

Beauty Dragon Haven

Dragon Haven The Hero And The Crown d-2

The Hero And The Crown d-2 A Knot in the Grain

A Knot in the Grain The Blue Sword d-1

The Blue Sword d-1 Beauty (v1.2)

Beauty (v1.2) The Door in the Hedge

The Door in the Hedge